About University Alliance

University Alliance (UA) represents leading professional and technical universities across the UK. Our members specialise in working with industry and employers.

Their teaching is hands-on and designed to prepare students for their careers. Their knowledge and research drive industry and the public services to innovate, thrive and meet challenges.

Alliance universities are leading the way in innovation and business support in the green, tech, and healthcare industries. They are major educators in healthcare, engineering, the creative arts, social sciences, degree apprenticeships and more.

We are ready to serve

Professional and technical universities stand ready to serve our nation. They have the “fresh thinking and new ideas” the government is looking for in abundance and should be at the heart of our national renewal. Alliance universities are keen to act as strategic partners with government and business, enabled by higher education sector representation on the Industrial Strategy Council.

In the past there has been a failure to fully exploit what universities can offer the country. Universities deliver on multiple fronts at national, regional and local level, but the policy landscape is often disjointed. If government takes a more strategic and joined-up approach to higher education, the sector will be better able to put its weight behind all five of this government’s missions.

In partnership with government and industry, professional and technical universities can:

- Work with businesses to innovate and deliver economic growth;

- Train the next generation of NHS, teaching and policing professionals so that our public services can thrive;

- Provide life-changing opportunities for a wide range of learners throughout their lifetime;

- Put Britain at the forefront of the clean energy revolution.

Below we outline how professional and technical universities can help create a better future for the UK with the right policies and practices in place. We set out impactful priority actions for the government to take in the short-term that cost little or nothing to deliver.

We also highlight additional steps that should be taken in the medium and longer-term to ensure that universities are in a strong position to help find solutions to our most pressing local, national and global problems.

Professional and technical universities can support the government’s five missions:

1: Kickstarting economic growth

- 1.1 Support innovative regions and SMEs

- 1.2 Grow the creative industries through education

2: Building an NHS fit for the future

- 2.1 Embed universities in NHS and social care planning

3: Breaking down barriers to opportunity

- 3.1 Address financial shortfalls for higher education students and providers

- 3.2 Develop a post-16 education strategy

- 3.3 Reform apprenticeships and skills policy

- 3.4 Enable universities to train more teachers

4: Taking back our streets

- 4.1 Police constable degree apprenticeships

5: Making Britain a clean energy superpower

- 5.1 Developing clean energy solutions through applied research

1: Economic growth

We support the government’s aims of unlocking the innovation and growth potential of our regions, making Britain the best place to start a business and investing in high-growth sectors such as our creative industries. Professional and technical universities specialise in university-business partnerships and can play an integral role in delivering these aims. We want to work in collaboration with national and local government to do so.

1.1 Support innovative regions and SMEs

To deliver regional growth we need a healthy research and development (R&D) ecosystem across the whole of the UK. This must include support for innovation within small and medium enterprises (SMEs), which are the lifeblood of local economies. Professional and technical universities specialise in SME support, equipping thousands of businesses every year with the capabilities they need to innovate and grow at scale. They also generate spinouts and help students and graduates to build their own start-ups. There is untapped capacity in professional and technical universities to do more in this space.

As a priority: Use the commitment to 10-year R&D budgets to launch a national conversation on R&D.

The commitment to 10-year R&D budgets will be a vital enabler for research organisations and the private sector to make more strategic decisions and investments. Despite our strengths as a nation, most of the public do not think the UK will be at the forefront of major breakthroughs. Long-term policymaking should not be seen as just a technocratic change. The government should use this opportunity to raise public consciousness of the role of R&D in society and the economy and the importance of public involvement in R&D.

As a priority: Set out a policy roadmap.

The government should signpost early on how it will sequence the planning and implementation of commitments on R&D, industrial strategy, devolution and skills. This would encourage join-up between overlapping interventions and help universities and other stakeholders marshal their expertise and resources effectively to contribute to these agendas.

In the longer term: Use local growth plans to refocus 'levelling up' funding on economic growth.

There was a missed opportunity to adequately embed research, innovation, and support for SMEs in the UK Shared Prosperity Fund. The government can rectify this through funding directed to achieve Local Growth Plans, focussing on improving skills, driving innovation and encouraging investment in each region’s growth sectors.

In the longer term: Scale up the higher education innovation fund (HEIF) and protect its scope.

HEIF represents excellent value for money and is a tried and tested way of increasing economic benefits from the work of universities. The new National Wealth Fund will have a target of attracting £3 of private investment for every £1 of public investment; the return on investment ratio for HEIF is £8.30 for every £1. The government should avoid overly hypothecating the use of HEIF on IP and spinouts at the expense of other important forms of innovation and entrepreneurialism that lead to commercial success. The data informing allocations of knowledge exchange funding in England, Wales and Scotland should capture deeper insights on how universities support workforce planning and upskilling.

In the longer term: Implement sustained, real-terms growth in the R&D budget

This should be accompanied by an increase in domestic public investment outside the Greater Southeast and a focus on how R&D can support inclusive economic growth within every region. The UK should be a leading country in the G7 on R&D investment, but we are currently lagging behind commercially successful research-intensive nations.

1.2 Grow the economy through the creative industries

The government recognises that the UK’s world leading creative industries hold potential for growth that would benefit every corner of the UK. The creative sector is the fastest growing area of the economy. It brings in £126bn in gross value added to the economy and employs over 2.4 million people. However, growth is being hampered by national skills shortages. The creative industries are not sufficiently embedded into the national school curriculum, and educational reforms over the past decade have put the creative pipeline at risk.

As a priority: Recognise creative subjects as qualifying subjects in the EBacc and Progress 8.

Since these narrow accountability measures have been introduced, there has been a precipitous decline in creative and digital subjects being taken at GCSE, for example design and technology (-80%), music (-36%), drama (-40%) and computing or ICT (-40%). This is seriously impacting entry to creative arts qualifications at level 3 and higher, particularly for the least advantaged learners.

As a priority: Ensure professional and technical universities have a seat at the table when developing the creative industries sector plan.

Nearly three quarters of those employed in creative occupations are qualified to degree-level or above, compared to 45% across all industries. Alliance universities are leading providers of creative arts and design degrees. Our partnerships with major employers from Adobe to Netflix mean that students are gaining industry-led instruction and creative skills that will drive the nation's future innovation and enterprise. Join-up between government, industry and universities is crucial to ensuring the sustainability of the creative pipeline.

In the longer term: Attract and retain specialist teachers across creative and cultural subjects.

Teacher shortages in creative subjects are particularly acute, and two thirds of art and design teachers are considering leaving the profession.

In the longer term: Restore high-cost funding to creative subjects.

These courses are expensive to deliver due to the specialist facilities, equipment and staff required. The 2021 cut to Office for Students (OfS) high-cost subject funding for creative arts, performing arts, and media studies subjects has disincentivised provision in these strategically important areas of the UK economy.

Case study: driving business growth in Birmingham

STEAMHouse, Birmingham City University

STEAMhouse is Birmingham City University’s innovation centre aimed at encouraging co-working and collaboration between the arts, science, technology, engineering and maths (STEAM) sectors to support sustainable economic growth, productivity and job creation. It is anticipated STEAMhouse will help create up to 10,000 jobs across the West Midlands.

STEAMhouse provides access to state-of-the-art facilities which businesses can access for free, including 3D printers, laser cutting machinery and virtual reality technology, as well as a comprehensive package of business support and has helped a range of innovators take their products to market.

Between its opening in 2018 and 2022 STEAMhouse had:

- Created 65 new enterprises, who have constructed 75 new products;

- Forged 27 linkages globally, including a new innovation centre in India;

- Delivered 34 research collaborations between businesses and BCU academics;

- Welcomed 18,000 visitors for events, workshops and using the workshop facilities.

2: NHS

The government is committed to ending the workforce crisis across both health and social care and delivering the NHS Long Term Workforce Plan (LTWP). To achieve this, workforce planning must actively involve universities at the national, regional, and local levels.

2.1 Embed universities in NHS and social care workforce planning

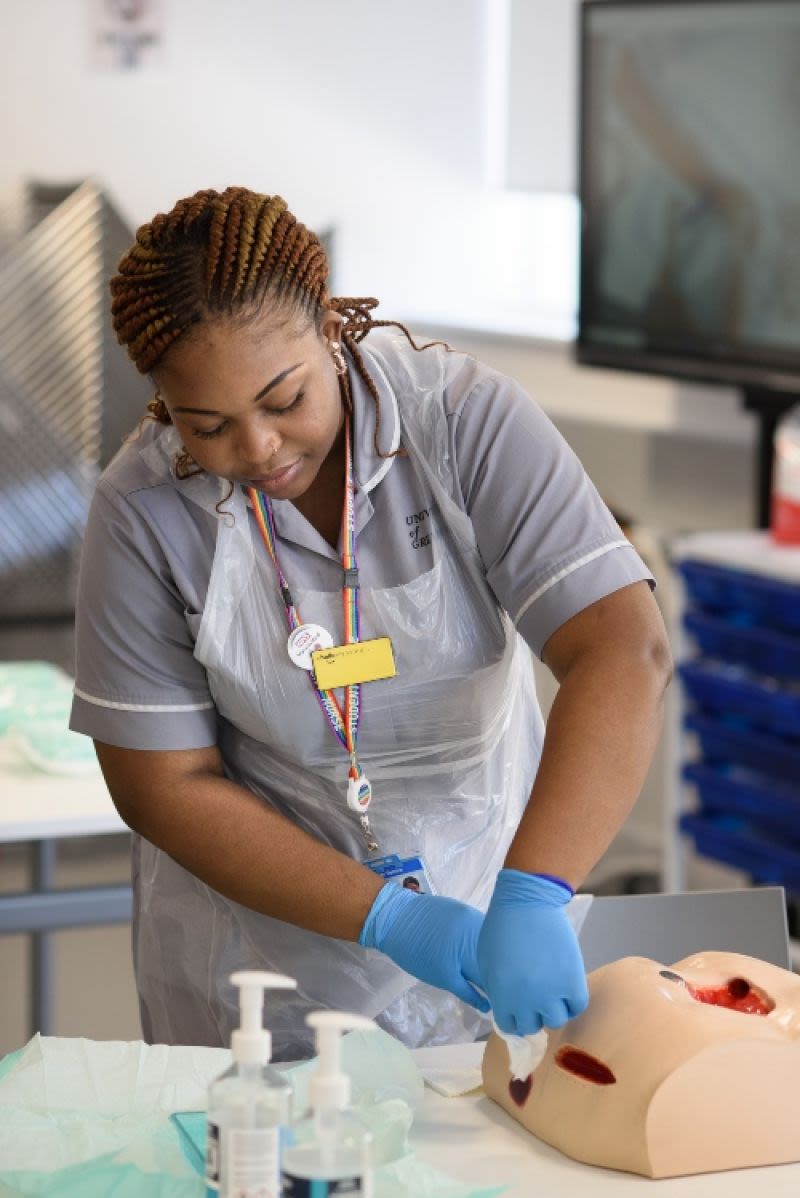

Alliance universities educate around 30% of all nursing students in England and a considerable proportion of allied health professionals and healthcare degree apprentices. We strongly support the LTWP and its objective to achieve the biggest workforce expansion in NHS history.

As a priority: Convene a cross-government health education task force to coordinate delivery of the Long Term Workforce Plan (LTWP).

Membership should include representatives from local and central government (including the Department for Education and the Department for Health and Social Care), NHS England, health regulators, professional bodies, and higher education.

As a priority: Issue guidance to ensure universities and colleges play a key role in Integrated Care Systems (ICSs) and Integrated Care Boards (ICBs).

We are calling for more strategic involvement of educators, especially in relation to the development of new roles, including non-healthcare roles, to deliver the healthcare workforce for the future and transform the NHS and social care.

In the longer term: Progress reforms to nursing and midwifery education outlined in the LTWP.

Alliance universities could educate significantly more healthcare professionals if our regulatory framework was based on outcomes and competency rather than time served. Reducing overly prescriptive practice hour requirements will free up much-needed placement capacity. We look forward to working with health regulators and the NHS to ensure that education and training requirements are fit for the future.

In the longer term: Provide access to additional capital funding for universities and colleges to invest in scaling up their simulated education and training provision.

Reforms by the Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC), which permit up to 600 hours of clinical placement to take place in a simulated setting, have enabled students to practice rare or risky procedures, as well as everyday skills, in safe but highly realistic environments, before using them on real patients. Continued support is needed to grow simulated provision – taking further pressure off clinical placement providers.

Case study: Innovative midwifery training in London and Kent

University of Greenwich

The number of midwifery applicants in England has been dropping in recent years and the University of Greenwich, working with thirteen NHS trusts in London and Kent, is leading the way by offering an alternative route for people to train as midwives. This is one of the first three midwifery degree apprentices in the country.

The dropout rate for the first cohort was zero, which compares favourably to undergraduate midwifery degrees. Following this resounding success, the university is planning to expand the programme for future years.

Abbie Hadlow, one of the first graduates from the apprenticeship, described her experience:

"The degree consisted of working in all areas of maternity and gaining experience in each setting. During each shift I worked alongside a practice supervisor who guided me and helped me to develop my skills to deliver quality care to women and their families.”

3: Opportunity

The government has recognised that UK higher education creates opportunity, supports local communities and is a world-leading sector in our economy. It has said that it views universities as a significant source of soft power and influence overseas. We strongly agree with government that anyone who wants to attend university should have the opportunity to do so. To maximise opportunity through education, the government must tackle financial barriers for students and universities, set a clear vision and strategy for higher education and skills and enable universities to train more teachers.

3.1 Address financial shortfalls for higher education students and providers

The government has recognised that higher education is currently in crisis, and that the current funding settlement does not work for the taxpayer, universities, staff, or students.

As a priority: Increase student maintenance support.

The failure of the maintenance system to keep up with living costs is affecting access to and success at university, with over half of students working part-time and a quarter at risk of dropping out. It is vital that maintenance entitlements and parental income thresholds are uprated to widen support to more families. Means-tested maintenance grants should be reinstated to end the perverse phenomenon of the least well-off students graduating with the most debt. Modelling demonstrates this can be done at no additional cost to the Exchequer.

As a priority: Ensure the UK can continue to compete as a top destination for international talent.

International students make a significant contribution to our universities, communities, the economy and the UK’s soft power. Effective immigration policy that clearly signposts the UK as a welcoming environment for international students is essential to the financial sustainability of UK universities. However, overseas applications have declined by more than a quarter, mostly due to political choices. We welcome the government swiftly adopting a different approach. As part of this reset, international students should be removed from estimates of long-term migration statistics. International students are not traditional migrants and should not be treated as such.

In the longer term: Restore the higher education unit of resource to the equivalent of 2015/16 levels as soon as practically possible.

Universities receive a third less per domestic student than they did a decade ago and make a loss on both research and teaching. As a result, 40% of higher education providers are expected to be in deficit in 2023/24. To put universities on a financially secure footing, the government must take the tough but necessary decision to increase domestic tuition fees; public investment in universities; or contributions from employers – or a combination of these.

In the longer term: Give universities greater flexibility to set their pension arrangements.

The employer contribution rate for the Teachers’ Pensions Scheme (TPS) rose to 28.68 per cent from April 2024, at a cost of £125 million per year to universities. The 80 universities affected are legally bound to offer TPS. A review of pension rules across the higher education sector would save universities millions at little cost to the Exchequer, while still offering staff a fair deal.

In the longer term: Conduct a review of all regulation that affects the HE sector to ensure it is proportionate and fit for purpose.

Universities are rightfully subject to robust regulation, but the current regulatory regime is disproportionate and costly, encompassing the Office for Students (OfS), Ofsted, and multiple Professional, Statutory and Regulatory Bodies (PSRBs). The House of Lords found this is leading to duplication and red tape. Burdensome regulation diverts university resources away from frontline teaching and student services. UA would like to see a more co-regulatory approach between OfS and other regulators to reduce unnecessary duplication and bureaucracy. Currently, the OfS is not sufficiently expert, politically impartial, or independent of ministers to be effective. We support the recommendations of the House of Lords Industry and Regulators Committee.

3.2 Develop a post-16 education strategy

The government has committed to bringing forward a comprehensive strategy for post-16 education. This is sorely needed. Education and skills policy is currently disjointed and lacks strategic direction. Meanwhile the UK faces numerous skills shortages and is at risk of falling behind its global competitors, who are making more concerted efforts to grow the number of people with higher-level qualifications.

The strategy should:

- Set out clearly the role the Government wants universities, colleges and other education providers to play in upskilling the nation and delivering growth and prosperity

- Aim to incentivise partnerships and pathways between different types of providers

- Encompass the research and innovation ecosystem

- Consider how to reverse the sharp decline in part-time and mature learners and instil a culture of lifelong learning.

We believe the strategy has the potential to form the basis of a new social contract between universities and society.

As a priority: Implement an immediate pause to the defunding of BTECs and other applied general qualifications.

AGQs such as BTECs provide an effective route to higher education and skilled employment, particularly for less advantaged learners. The focused review of qualifications (including AGQs) due to conclude by the end of 2024 does not provide schools and colleges with the certainty they need to plan what they can deliver in 2025/26 and to provide effective information, advice, and guidance to prospective students. To avoid young people being disadvantaged by these reforms, the government should urgently confirm that students will be able to enrol on all existing AGQs up to and including the 2025/26 academic year.

As a priority: Put mechanisms in place to ensure effective join-up between higher education teaching, research and innovation.

With responsibility for higher education teaching and research split between two ministers and departments, there is a need to ensure the government takes a holistic view of higher education, research and innovation that recognises the economic contribution of universities.

As a priority: Reverse cuts to foundation year fees.

The planned fee cap for OfS Price Group D subjects will reduce the availability and choice of integrated foundation year provision, which has an excellent track record of enabling progression to higher level study. This will compound the negative effects of early specialisation that is a feature of the post-16 system, particularly for disadvantaged learners and those with special educational needs.

As a priority: Establish an independent expert panel to help develop, implement, and champion the post-16 education strategy.

It is crucial that the strategy is developed in consultation with a wide group of education and training stakeholders, including professional and technical universities.

In the longer term: Align the post-16 education strategy with a higher education funding model that is fair to students, providers and the taxpayer.

A lack of strategic policy direction for higher education and a sustainable long-term funding settlement are currently inhibiting investment and planning in universities. The development of a new strategy offers a chance for a rethink of the funding model to ensure it is fair and effective at meeting the government’s wider objectives.

3.3 Reform apprenticeships and skills policy

The government wants to see high-quality apprenticeships and has committed to reforming the Apprenticeships Levy and establishing Skills England to coordinate regional priorities and align skills policy with wider ambitions. We welcome these steps and urge government to ensure that any action they take supports growth in the number and diversity of enormously popular higher and degree apprenticeships.

As a priority: Give Skills England a clear remit and objective to cut bureaucracy.

Higher and degree apprenticeships are caught in a tangle of regulation and unnecessary bureaucracy, which is hampering innovation and dampening growth. The fact that they grew by 190% between 2016- 2022 is a testament to their value and potential. The creation of Skills England, with its convening power and wide-angle, long-focus lens, should be used to meaningfully cut bureaucracy whilst maintaining quality.

As a priority: Commit to expanding the consultation on the Growth & Skills Levy.

A public consultation on eligible courses is an opportunity to dig deeper with a wide range of stakeholders and mitigate unintended consequences. This should include how to protect apprenticeships that are being put to great effect to train and retain staff at all ages and stages from a potential funding shortfall (particularly in the public sector and other growth sectors); how the government will continue to contribute 95% of the training costs for small businesses if demand for funding meets or exceeds what is raised from the levy; how to increase transparency from government about how levy funds are managed and spent; and whether the levy should be widened at a lower rate for more employers.

As a priority: Remove the cap on Apprenticeship Levy transfers in the meantime.

This will allow levy payers to support small businesses in their supply chains or help address local skills gaps.

As a priority: Commit to applying a credit value to all post-16 qualifications to support lifelong learning.

Applying a credit value is a means of quantifying and recognising learning whenever and wherever it is achieved. As a first step, the government should encourage the Institute for Apprenticeships and Technical Education (IfATE) to introduce an approach for Trailblazers to assign both a credit level (as they do currently) and a credit value to new apprenticeship standards.

As a priority: Factor universities into plans to reform the inspection regime.

As an interim step towards more effective, contextualised and collaborative regulation, the government should ask Ofsted to immediately designate all higher education providers as “large and complex providers” so they are subject to the 5-day extended notice period for inspection of higher and degree apprenticeships.

In the long term: Establish an equitable and simplified approach to funding.

Degree apprenticeships are costly to deliver, in part due to several funding bands being set too low. The government should explore using the credit value established through the preliminary work on the Lifelong Learning Entitlement (LLE) to introduce a common approach to funding higher education provision, including degree apprenticeships.

3.4 Enable universities to train more teachers

The government plans to recruit an additional 6,500 new teachers. It has committed to reviewing bursaries and retention payments, improving the Continuing Professional Development (CPD) offer and raising the status of the teaching profession. As the primary educators of teachers, universities have a wealth of experience and solutions to offer.

As a priority: Ensure universal geographical coverage of teacher training opportunities by adding a third phase to the Initial Teacher Training (ITT) market review accreditation process to allow for “near miss” providers to achieve accreditation.

One of the immediate and direct impacts of the ITT market review and resulting accreditation process was the loss of universal coverage of accredited providers. This is now directly compounding the teacher recruitment shortage in specific areas.

In the longer term: Develop a programme of financial incentive and reward for teacher training.

As the government has acknowledged, there needs to be a considered look at the whole fees, grant and bursaries system around teacher training to truly reward and incentivise applicants.

In the longer term: Reform and restructure the teaching profession to allow for more flexible working and more professional development opportunities.

Recent research has found that reducing teachers’ working hours and workloads is likely to be the most effective method of stopping teachers leaving the profession. Retention is also closely linked to senior leadership quality.

Case study: University-business partnerships delivering opportunity in Derby

Nuclear Skills Academy, University of Derby and Rolls Royce

The Nuclear Skills Academy is the first of its kind and aims to sustain nuclear capability within the UK’s submarines programme by creating a dedicated pipeline of talent at the start of their careers. The academy offers degree apprenticeships alongside level 3 and 4 apprenticeships.

Based in Derby, the Nuclear Skills Academy is a partnership between the University of Derby and Rolls-Royce supported by industry and education experts, including the Nuclear Advanced Manufacturing Research Centre, the National College for Nuclear and Derby City Council.

Matilda Matthews, one of the first apprentices to join the academy, described her experience:

“During my time in the Nuclear Skills Academy, I have built my knowledge and gained experience thanks to the support of senior members of the business, as well as from teachers. My knowledge of the engineering world is constantly developing and strengthening.”

4: Our streets

4.1 Police Constable degree apprenticeships

The government has pledged to recruit thousands of extra police officers to help restore neighbourhood policing. Training and continual professional development is a vital part of ensuring the workforce has the necessary talent and culture to respond to the complex demands of modern policing. The well-established Police Constable Degree Apprenticeship (PCDA) is utilised by twenty-one police forces in England and Wales and is mostly delivered by universities, including seven University Alliance members and the ground-breaking Police Education Consortium.

However, the PCDA has been destabilised through a policy disconnect within the last government following the decision to end the compulsory roll-out of police degrees and statements promoting non-degree routes for policing. To ensure parity with other high-skilled professions and enable growth in police training provision, the government should review this decision, as well as cutting the bureaucracy surrounding higher and degree apprenticeships (see section 03.3).

Policing is also just one example of how technical and professional universities are leaders in translating their research into improved services and societal impact. For example, Anglia Ruskin University, one of the leading universities for police education in the UK, established the International Policing and Public Protection Research Institute (IPPPRI). The IPPPRI provides opportunities for academics and police practitioners to exchange knowledge and maximise the impact of research into policing and public protection on policy and practice.

Case study: police training partnerships across the South East

Anglia Ruskin University

Anglia Ruskin University is one of the leading universities for police education in the UK. They deliver training for police forces across the East of England and the South East.

One such training programme is the Police Constable Degree Apprenticeship, where new Police Constables enrol on a three-year course, combining a degree programme with on-the-job training.

PC Griffiths is a Metropolitan Police recruit at Anglia Ruskin’s East London campus and is taking the three-year police constable degree apprenticeship (PCDA). The course fully funded by the Metropolitan Police and apprentices are paid a starting salary of £36,775, gaining a degree in professional policing practice on completion.

“Here, you get that [your tuition fees] paid for and you come out with a degree at the end of it," said PC Griffiths. “I would recommend this course to anyone, even those who don’t think of themselves as academic and haven’t considered doing a degree.”

5: Clean energy

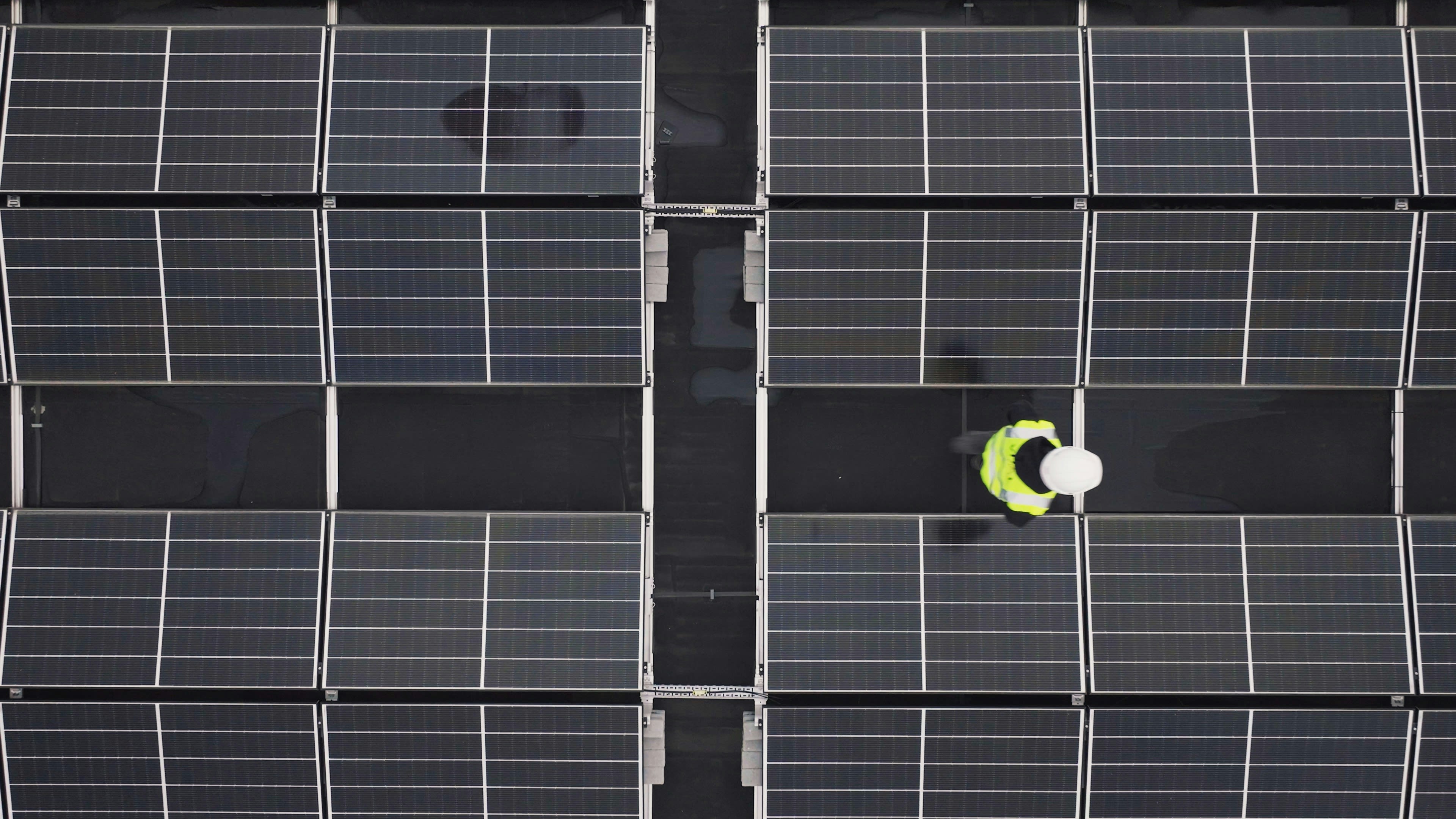

5.1 Developing clean energy solutions through applied research

The government recognises that the UK’s universities offer an untapped advantage to enable the country to become a clean energy superpower. UA and our members are keen to work closely with the government, including through representation on the Industrial Strategy Council, to deliver a clean energy revolution.

Professional and technical universities are not only training the workforce that will be required to meet this ambition, they are also undertaking urgent, applied research that addresses multiple challenges created by the climate crisis. This is focused on making a difference for people in their everyday lives through new products, innovations, creations and driving behavioural change. For example, Robert Gordon University is working closely with industry in the North Sea to advance the transition to a sustainable, low-carbon energy system.

The Net Zero Industry Innovation Centre (NZIIC) at Teesside University is helping to create hundreds of clean energy jobs in the Tees Valley. Its work to date has included groundbreaking research into how to reduce the carbon footprint from waste-to-energy (WtE) plants and it is collaborating on an innovative hydrogen transport project, which will see fleets of zero-emission trucks, powered by hydrogen fuel cells, being deployed across the region from the mid-2020s.

A Dolphin N2 engine developed at the University of Brighton is one of the cleanest high-efficiency engines that exists in the public domain. It uses sustainable fuels made from everyday wastes and has the potential to reduce emissions from heavy duty vehicles, diesel trains and ships.

Carbon8, a spinout from the University of Greenwich, is a global leader in carbon capture, utilisation and storage (CCUS), specialising in mineralisation. The company helps industry decarbonise while transitioning to a more circular operation.

These are just a few of the examples of game-changing research being done at Alliance universities to develop clean energy solutions. In addition, UA’s energy doctoral training programme is producing the next generation of energy experts with the skills and experience to tackle the global challenge of ensuring future security and sustainability of energy supplies and the management of energy demand.

Case study: clean energy driving growth in Teesside

Net Zero Industry Innovation Centre, Teesside University

The Tees Valley is responsible for almost 50% of the UK’s production of hydrogen, and innovation in this sector is predicted to be a huge driver of economic growth in the region.

The Net Zero Industry Innovation Centre (NZIIC) at Teesside University brings together expert insight, resources and partnerships to grow net zero capabilities and opportunities, placing the Tees Valley at the forefront of the clean energy agenda and helping to create hundreds of clean energy jobs.

Their work to date has included groundbreaking research into how to reduce the carbon footprint from waste-to-energy (WtE) plants , which will have a huge impact on the region’s decarbonisation efforts. They are also collaborating on an innovative hydrogen transport project, which will see fleets of zero-emission trucks, powered by hydrogen fuel cells, being deployed across the region from the mid-2020s.

Case study: attracting investment into green technologies

Carbon8, spinout from the University of Greenwich

Carbon8 is a global leader in carbon capture, utilisation and storage (CCUS), specialising in mineralisation. It span-out from the University of Greenwich.

Through their Accelerated Carbonation Technology (ACT), the company helps industry decarbonise while transitioning to a more circular operation. They capture CO₂ directly from the source to treat industrial residues and manufacture new materials. The captured carbon is locked into innovative, low-carbon products like lightweight aggregates, CircaBuild and CircaGrow.

In June 2022, Vicat Group, the international cement group, EDF Group and its corporate venture capital arm, EDF Pulse Ventures, co-invested £4m in Carbon8.

Thank you for reading

If you would like to discuss our recommendations, or want to work together, please contact us at press@unialliance.ac.uk